A few weeks ago I began a 7 month program run by the Trauma Research Foundation. I’ve decided life’s short and Bessel van der Kolk isn’t going to be around forever, so best to learn directly from the man while I still can.

Going back to school feels familiar and exciting at the same time, satisfying in a strange way. There’s a new lecture each week and occasional Q&A sessions with faculty, which has been manageable thus far.

What I haven’t factored in is the emotional tax. With each module the picture of trauma grows bigger and darker, a shadow that envelops me while I fill my notebook with bullet points and questions circled in red. I’m on a guided tour of the precipice that almost swallowed me, and l survey the crime scene collecting evidence for a case that will never go to court.

The still face experiment comes up a few times.

A mother and her toddler are playing. The little boy is happily going back and forth between mum and his toy dinosaurs. Suddenly the woman stops moving or making eye contact, as if she’s turned into a statue.

The boy pauses, disconcerted. Getting mum back online becomes his central focus. He calls her name, pushes toys in her hands, climbs in mum’s lap in a one-sided, pleading cuddle. You can hear his distress in the rising pitch of his voice.

The woman resumes normal behaviour after 2 minutes.

The boy in the still face experiment has learnt that relationships come with glitches, moments of rupture, but also repairs. Happy endings. He’ll never have an explicit memory of this bizarre episode. Yet long after the experiment, he is brought in the same room and his cortisol levels go slightly up.

I squirm in my seat, I avert my eyes. For days I keep thinking of the little ones whose mums were never really there and learnt a very different lesson.

In another module we go over the case study of a severely traumatised boy, who at least had the fortune of being in the care of a trauma competent therapist.

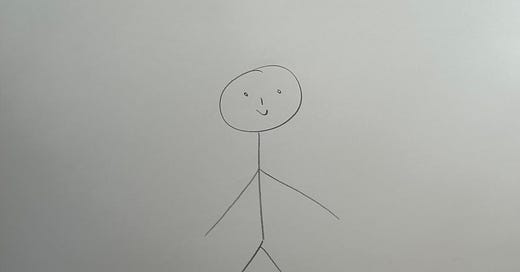

The boy cannot talk about what happened to him, but he can draw. He’s asked to make a picture of his family, and everyone looks like this:

I’m not sure what to make of it, I don’t spot anything unusual because that’s how I’ve always drawn too.

As the boy progresses through therapy his drawings gain bodies, clothes, fingers and shoes. Eventually they even smile and hold hands.

Good for him, I think.

Is it bad that mine never did?

I ask my son to draw himself and thankfully he produces a full bodied silhouette. There’s a numbered football shirt, a ball, goal posts and grass, and I sigh with relief.

Children don’t have a language for their trauma, and guess what, many adults don’t either.

Even when the facts and memories are accesibile, the language cannot do them justice. Alexithymia - the diminished ability to fully get in touch with, identify and articulate our feelings - is a common challenge for complex trauma survivors.

And is that any surprise? When survival depends on masking your pain for years, when no one cared enough to help you make sense of your emotions - how do you end up any different1?

Perhaps that’s one of the reasons survivors do not speak enough about their traumas and for themselves (aside from the paralysing shame and fear of being deemed broken beyond repair). Perhaps they simply do not have the words for it.

But through it all I notice changes, small victories I add under my belt:

feeling the familiar pressure rise when the kids shout, jump, demand snacks and water, cover the floor in crumbs and spill said water, want me to read a book and play with them all at once while I build the groceries shopping list and pack the school bags, and instead of blowing up deciding they’re just children being children, life’s busy and messy and taking it one thing at a time

being surprised by a sudden gesture, reaching for a defensive reaction and seconds later being able to re-interpret it and respond in a friendly manner

spending less time thinking about everything that can go wrong, and more time just being here and now

filling out a personality questionnaire and no longer doubting my answers, finally having a sense of who I am.

Are you moving forward as well? I hope you are and I would love to hear about it in the comments.

Thanks for tuning in,

Adina

I look at alexithymia here through the lens of complex trauma, but the condition is not limited to trauma survivors and its development is not fully elucidated.

I've had so many of these realisations myself recently. I still don't have words for many of the things I experienced as a child, but I'm slowly learning that I can express things in many different ways, which is why I paint now. Finding my voice has been a very different experience to what I imagined, and an incredibly difficult one, but I'm so glad I'm able to persevere.

Thank you for sharing this; so much of it resonated, and that's always a gift to me.

I admire you for pursuing this important info. Everything "trauma related" is waiting for you. Keep this up and the work will find you!